Words by Roger Upton

Published in 2010, Arab Falconry: History of a Way of Life is by esteemed writer Roger Upton, better known in Arabian horse circles for handling the much-admired stallion Hanif (Silver Vanity x Sirella), as well as being the twin of Peter Upton. The link between Arabian culture and falconry is well known and in this world edition of The Arabian Magazine, we share a chapter from Roger’s beautifully illustrated book, as well as his emotive introduction. Arab Falconry: History of a Way of Life is available to purchase from The Arabian Magazine – please see the information at the end of this beautiful piece.

Falconry is rich in literature, with books and manuscripts in many languages. In the West the flow of books and articles on the subject continues unabated, much of it only repeating what has been written before. In the Middle East, where so many early manuscripts originated, little has been written in recent years of the art and practice of falconry among the Arabs.

Short articles have appeared from time to time in the West on Arab falconry. A chapter or two in travellers’ books have added to this fragmentary knowledge, but other writings have been inaccurate and have only touched upon the fringes of the subject, much to the frustration of falconers and sportsmen in the West, many of whom are fascinated by falconry in Arabia. If they are seen by Arab falconers, these references to their sport interest them but little, and rather amuse them than annoy them by their inaccuracies.

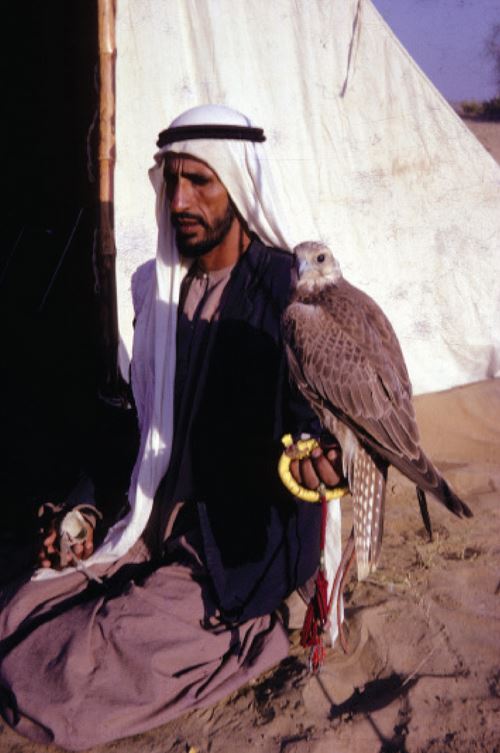

|

| The author with his favourite peregrine, Ablah. |

In 1980 an excellent book was published, Falconry in Arabia by Mark Allen. This well-produced volume satisfied some of the curiosity that existed about the subject and contained much of interest. However, it was not, nor I believe was it intended to be, an in-depth study of the details, the ingredients and the interesting differences to be found in the varied terrain and different countries in Arabia and elsewhere where Arab falconers still pursue their favourite sport.

I use the word ‘sport’, for although it could be said that to the Arab falconry is more a way of life, a tradition, rather than a passing interest, it is important to present-day falconers that it should be sporting. They get pleasure from a high flight which taxes a falcon to the utmost and they appreciate the value of the sporting element compared to the exciting but less sporting capture of a houbara bustard, that has never left the ground, a few yards away from the car.

I now realize how very fortunate I was to have journeyed to Arabia before the great changes swept aside much of the old way of life. When first in Abu Dhabi we hawked in the desert only an hour or so from the island town, or rode out on camels from Buraimi finding quarry, if not plentiful, at least available in scattered numbers and enough to hunt with our five or six falcons. Once we caught a desert hare on Abu Dhabi island where the Hilton Hotel now offers handsome rooms to international businessmen.

|

Within a few years, sheikhs and princes began travelling abroad in huge hawking parties with many hawks, to Pakistan, India and Iran, there to find houbara, the premier quarry of the Arab falconer, in undreamt of numbers in ideal hawking country.

Once again I was fortunate in being invited to hawk with my good friends in these countries, where we found houbara in their hundreds.

The more we talked around the camp fires of trapping and training and sport, the greater was my desire to travel with trappers to remote places, to see the lovely fresh-caught hawks at the houses of merchants in Damascus, Lahore and Riyadh and to try to learn something of the skills of Arab falconers from all parts of Arabia. Since then I have made friends from Syria to Saudi Arabia and from Pakistan to Morocco, while learning of trapping and sharing the camp fires of many hunting camps.

Over these 50 and more years I have seen many changes, and have had the opportunity to record those many small details perhaps only obvious to a fellow falconer. Likewise, by studying the translations of earlier writings such as The Baz-Nama-yi Nasiri, written in 1842 by Taymur Mirza, I have found a fascination in comparing the methods and views of long ago with those of today.

As if piecing together the many parts of a huge jigsaw puzzle, I have attempted to sort out as best I can the many notes, thoughts and comments on Arab hawking. I am still unsure whether I have mislaid any pieces or perhaps inserted them in the wrong place in the puzzle. From my untidy but detailed diaries, old articles, past treatises and present-day experiences, I have, I hope, put together a readable story from which interested readers might learn something from what has been written.

Roger Upton

The Arab and Falconry

The increasing appetite for oil in the industrial West rudely awakened Arabia from a medieval mood of indifference to the world about it, isolated for so long by their deserts, their ever-changing borders and their nomadic wanderings. The rest of the world had been equally indifferent to the Arabs, their lands and their way of life, with the exception of a few travellers such as Burton, Doughty, the Blunts and Thesiger. Without the lure of oil and the greed that it creates, the industrial world would still be largely indifferent to the dust and the deserts of Arabia.

The great wealth created by the gushing oil wells brought rapid change to the old ways of life, but through it all, despite the influences and interference from abroad, many of the traditions of Arabia and of the bedouin have survived. One of these great traditions is the art and practice of falconry.

Since pre-Islamic times falconry has played a major part in the calendar of Arab life. With the cold winds of autumn came the first of the passaging falcons on their migrations from breeding grounds in the north. The Arabs, from royal prince to bedouin, then, forgetful of all else, would give all their time to obtaining the best possible falcons for the imminent hunting season. Trappers would travel to favoured areas, there to test their cunning against that of the sakers, lanners and peregrines so necessary to their sport.

Before long, tents and bazaars would be full of falcons of every description, some caught locally, others from far-distant and secret places, all to be trained and flown in the traditions of Arab falconry. For many centuries this annual experience remained little changed. Autumn would bring the passaging falcons and soon would come word from the bedouin tribesmen that the houbara bustard had arrived, the local populations supplemented by great numbers arriving from further north. So it was that both the houbara, and the passaging falcons arrived in the deserts of Arabia.

|

| Abu Dhabi 1964 – a large saker falcon. |

The influence of oil wealth quickly brought a change to the desert and to the old ways. All-terrain vehicles opened up the great deserts as never before, and the vast lands once almost unvisited except for drifting bedouin with their flocks and herds were now all within reach of the falconer in search of more houbara. Wealth brought more and more guns, and gazelle hawking with skilfully trained saker falcons and silky salukis became a memory as gazelles became scarce, even in the remote lands that were once their reserves.

Goshawks, once highly favoured by Persian falconers, were forgotten and in a single generation falconry all but disappeared in Iran. Only in the far north of Arabia, in Syria, are sparrowhawks still trapped each year to be flown at quail by a few devoted enthusiasts, although the practice still has many followers in Turkey, where for centuries sparrowhawks have been trapped, trained, hunted at quail and released at the end of the season.

However, the traditions of falconry were not to be easily lost in Arabia. There the houbara bustard, the stone curlew and the desert hare are still hunted with falcons in the Emirates, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Jordan and Syria, although many falconers from these countries now travel to other lands where houbara and stone curlew are more plentiful.

The roots of many Arabs lie deep in the deserts, bound up in the nomadic life of camel herds and black tents. A nomad’s life was social, with little privacy. He was never lonely, invariably in the company of others, at peace or in war, at rest or at play. The hawking camps still cultivate this togetherness and comradeship, among prince, sheikh and falconer. The traditions of Arab hawking knits them together, living together, working together, creating a special relationship, of understanding, tolerance and frankness that is very much a part of Arab history.

Arab hawking is rarely done alone. It is a joint venture in which all play a part, enjoying the simple pleasures of the sport, laughing together and sharing its excitements and disappointments. A hawking party might bring together as many as 200 men or as few as six or seven, but whether it is a large or a small party, the same friendly and cheerful atmosphere, together with the ever-optimistic attitude of the men, helps to maintain at least a part of the great traditions of the Arab way of life now fast disappearing. The successes and failures of the various hawks at their quarry, the expectation that tomorrow many more houbara are sure to be found, the evenings about the camp fires where everything is discussed and argued over, the folk stories prompted by the atmosphere of the camp, the jokes and laughter, these are all part of the tradition of Arabic hawking and without these ingredients the dish would not taste so well, and Arab hawking would be the poorer.

However, there have been changes. In earlier times there was a greater abundance of quarry. Moreover, time somehow seemed more generous and with little else to do and hawks kept in smaller numbers, falcons were undoubtedly trained to a greater degree of obedience. Disobedient hawks were all too easily lost, for if the falconer was mounted on a camel or horse, or following on foot, a wandering falcon was soon beyond recall. Today with fast-driven specialist vehicles and, as a last resort, the use of radio telemetry with which a lost hawk can be traced over many miles, it is possible to fly hawks that are nearly wild, in a high condition and very strong, so that in their strength they can fly high, wild and fast at the strongest, far distant houbara, which in earlier times would have been ignored.

|

Today, the populations of the main quarry species are greatly reduced, largely because of habitat deterioration but partly, it must be admitted from over-hunting. However, the numbers of houbara bustard, stone curlew and hares still to be found do not suggest that they are in any way endangered species. Some localized populations might be under pressure but over all the range countries, the populations of all three quarry species are generally still to be found in reasonable numbers.

Undoubtedly these populations fluctuate, influenced by habitat conditions and the density of hunting. When conditions are ideal, with a plentiful food supply influenced, of course, by rainfall, numbers increase surprisingly rapidly. This is particularly noticeable in the non-migratory populations of houbara in North Africa. What is undoubtedly true is that despite the constant hunting that has taken place over many years now, the houbara in particular seems very capable of holding its own, and falconers today still find them in sufficient numbers to make it worth the great expense of mounting a large hawking expedition. Whether this situation will continue remains to be seen.

Arab hawking involves the flying of wild-taken hawks at the natural quarry to be found in the desert: the houbara, the stone curlew and the desert hare. Traditional Arab falconry thrives upon the atmosphere of the camp and its people, the traditional way of handling and training their falcons and the pursuit of wild quarry in the sort of terrain in which the far-ranging flight can be followed by car.

There are those that assume that the supply of suitable hawks could be better met by captive breeding rather than taking falcons from the wild. However, there is no reason why hawks should not be taken from the wild, provided that such a take does not endanger these wild populations. After all, throughout the West we accept that sportsmen may kill what is classed a cullable surplus from many quarry species. Of course, without careful monitoring, it is difficult to obtain an exact picture of what effect the annual take has on breeding populations. But the numbers available in the suqs and bazaars of the Middle East each season over many years must reflect the general situation at the breeding sites. The prices demanded for these falcons must also give an indication of the numbers available each season. Supplies generally seem fairly constant and prices, if anything, have come down somewhat in recent years.

It should be remembered that many of these hawks find their way back to the wild, to slot into the spring northern migration, hopefully to pair and breed. Before the advent of radio telemetry many falcons were lost while hunting, often not so very far from where they were originally trapped. In earlier times especially, many of the falcons still in the tents were released back into the wild at the end of the hawking season. Only the best were considered worth the trouble and expense of keeping through the long summer months for use the following season. Today more are kept through the summer, although most falconers admit that it is among the new entry of falcons each season that they look for the best performers at high-flying quarry.

Captive breeding, properly done, produces hawks perfectly capable of taking houbara bustard along with the best of the wild-caught hawks. But, as with all eyasses (young hawks taken from the nest either in the wild or from breeding chamber), they require much greater time and effort in their training and entering to quarry than does the average passage hawk. When they are first flown at quarry, it is to be expected that, even if willing to take on so large a bird as a houbara bustard, they will make many clumsy mistakes with their first attempts at footing them, and will at first fail to get up over a flying houbara, rather attacking from below, which is never as intimidating to the quarry. However, given time, some eyass falcons have proved capable of flying houbara with the same success as their wild-caught brethren. Unfortunately, time is usually pressing for Arab falconers, opportunities are limited and the hunting season is of short duration. Meanwhile their passage and haggard hawks are taking quarry daily and so the ignorant eyass rarely has the opportunity to show what she could do with more experience.

|

| A Haggard peregrine. |

There is no doubt that the passage or haggard falcon is ideally suited to the methods and timing of falconry in Arabia. The migration is perfectly timed to produce a selection of suitable and already somewhat experienced falcons at just the right moment, allowing enough time for concentrated and expert training so that they are ready for the houbara which arrive with the colder weather so suitable for flying hawks in a country that, most of the year, is too hot for practical falconry. It would be the perfect arrangement if more of these lovely falcons, in particular the haggards, could be released at the finish of the hunting season, as they were in past times. Then the falcons would be, as it were, on loan from the wild for a matter of four months or so, little more than a hiccup in their life cycle.

Where the survival of Arab hawking is likely to stand or fall is not in the availability of hawks suitable for the purpose, but in a sufficiency of quarry, particularly the houbara bustard, at which to fly these lovely falcons. Without houbara there can be no traditional Arab hawking.

|

It is to the survival and possible increase in the widespread populations of the houbara that energy must be increasingly turned to ensure their future, and with it the continued practice of Arab falconry. Already much time and money is being spent on houbara research, but only if falconry survives will there be sufficient interest for this effort to continue.

So it is that, depending on one another, the houbara and the traditions of Arab falconry hopefully will continue to co-exist and the magic of the hunting camps continue to be a special experience, a moment in time, for many years to come.

Arab Falconry: History of a Way of Life is available in hardback, 224pp. The book retails for £35 but we are offering it for £30 plus p+p until 31 March.

To purchase a copy of Arab Falconry: History of a Way of Life or any of the books in our shop, please visit www.thearabianmagazineshop.com. Alternatively, you can send a cheque for the correct amount to the usual address.