Words by Anabel Jay

Photography by Catherine Spearing

The regeneration of rare a breed

Research source: Los Hispano-Arabes en la Yequada Militar by Commander Juan Manuel Lopez

The Hispano-Arabe (Ha’) has its origins from two pure breeds, namely the Spanish and the Arabian. Its earliest conception as a breed in Andalusia dates to the Muslim invasion of the Iberian Peninsular. In 1883, formal deliberate creation of, or selection for, the breed started in Spain, alongside the importation of Arabian horses in order to upgrade and expand other horse breeding programmes. There are some archive records showing earlier Hispano-Arabe breeding studs, as far back as 1778. From those early days, despite its popularity as a working cattle horse and military mount, expansion and consolidation as a breed has been slow.

This has been in part due to lack of quality of stock in some of the earlier breeding lines and the popularity of its own thoroughbred part-bred, the Tres Sangres or three bloods: the Anglo Hispano-Arabe (Aha’). They proved very popular for the military as a cavalry and sports horse and were also in demand by the cattle breeders for working livestock. These factors and increased national and international demand for the Pure Raza Espanola (PRE) led to the Hispano-Arabe breed dwindling in number and, effectively, by the mid 1980s it became a minority rare breed. In 1986, the Hispano-Arabe was officially given consideration as a breed requiring special protection and consequently given their own Stud Book.

|

In 1990 the Cria Caballar, a division of Spain’s Department of Defence assigned responsibility for breeding and rearing equine youngstock, started a number of strategies on military stud farms to conserve several indigenous breeds of equines and to aid the recovery and improvement of the Hispano-Arabe breed. Due to the very small numbers of Hispano-Arabe mares, an urgent breeding strategy was implemented to increase the number of Hispano-Arabes being produced using PRE and Pure Raza Arabian (Pra’) mares to produce (F1) 50% generation Ha’.

Starting with a small established handful of broodmares, a recovery and improvement plan for the Ha’ breed was based on two strategies. Firstly, the selection of stallions to be used, setting their breeding spell to last four to five years, revisable every two years, and weighing up which stallions should cover the new mares. Secondly, to define the aptitude tests to apply to the new generation of mares and stallions, allowing for the changes due to breed out-crossing in the recovery programme, but retaining acceptable requirements for registration and subsequent valuation, grading and approval for future breeding.

From 1992 to the present day, Spain’s plan for the recovery and improvement of the Hispano-Arabe breed has passed through three stages and is currently nearing the end of its fourth stage.

Stage 1 1992-1995

Marked by the use of foundation Ha’ stallions bred with (F1) 50% mares (out of PRE dams and by Pra’ sires).

Stage 2 1996-1999

Five selected Pra’ stallions were used to cover Ha’ mares and one PRE stallion selected to cover Pra’ mares.

Stage 3 2000-2005

Dominated by the use of PRE horses covering more than 80% of the Ha’ mares.

|

There was also a breeding programme dedicated to producing Ha’ F1 stock from PRE mares being covered by both Pra’ stallions and five new generation Ha’ stallions of 50% and 75% ratios, where the ratio refers to amount of Arabian blood. One military herd of Pra’ mares were also covered by PRE stallions, as this cross had not been used too often in previous stages.

Alongside these controlled breeding strategies, some mares were freely covered by Hispano-Arabe stallions to produce quality F2 and F3 stock to progress and improve the breed.

Stage 4 2006–present day

Designed to deal with the matured F2 stock with the 62.5% and 37.5% Arab blood that, in earlier stages, was very difficult to find but is the natural progression of outbreeding the 25% and 75% Ha’s to PRE or Pra’. Ha’ stallions and Ha’ mares of these ratios bred to each other produce 50:50 fixed geneotype Ha’s.

The second strategy for the breed’s recovery and improvement, looking at defining tests to evaluate the qualities in the Hispano-Arabe’s being produced through this programme, had to ensure that they reflected the breed standard.

Initially the military training centres applied the same tests to the Hispano-Arabe as those devised for the Anglo-Arabe (Aa’), another breed project they were working on. As they gained experience, a different set of tests evolved for the Hispano-Arabe, assessing them in conformation, temperament, trainability and ridden abilities from foals to mature ridden horses.

|

The military modified their initial strategy when a young 50% Hispano-Arabe stallion Ultraje proved himself qualifying and completing tests for ANCADES (Associacion Naccional por Caballos Desportes, the Spanish Sports Horse Association) obtaining very promising results. Now future stallions are expected to demonstrate that they pass their quality and abilities onto their offspring in the same way other breeds do without, in principle, resigning the breed to any specific equine discipline. In effect, the Hispano-Arabe is to retain the qualities that made it a versatile working horse and show aptitude to become an all-round sports horse. In this respect, the Cria has continued a project that they started in about 2006, in collaboration with several military horse farms, to compare the Hispano-Arabe stallions in recruitment for sports competition. At the time that Commander Lopez produced his article on the recovery programme, he noted that the Hispano-Arabe stallion Relampago from Jerez was already involved in a career as a competition sports horse.

It is important to note that alongside this plan for the recovery and improvement of the Hispano-Arabe exists the premise, year after year, that all decisions taken by the Technical Advisory Board (the Junta) regarding the military stud farm mares is, by necessity, a drastic selection process. Apart from helping in the recovery of a breed, the studs involved must determine the Hispano-Arabe model that will be present in any horses of the breed produced elsewhere.

The implication being that, in future, the selection of stallions and mares will become far more demanding. The original article Commander Lopez wrote was aimed at and taking consideration of the Spanish Hispano-Arabe breeders, predominantly the ranchers and cattlemen for whom this breed is so vital.

He noted that the requirements of the military for an exceptional sports horse exhibiting beauty and distinction as well as the greater bone development and seriousness for the competition discipline had to coexist with the requirements of the cattlemen for “a horse of great nobility that makes daily handling pleasant, without being sluggish, the requirement for a comfortable ride, a good mouth, endurance and a great capacity for learning”.

His article concluded with a postscript referring to the important changes affecting the Cria Caballar in Spain; this would be in reference to the changes we have seen regarding the PRE and the importance of cattle ranches becoming proactive in promoting the reputation of the breed, and to take serious measures to recreate the breeding stages for their Hispano-Arabe mares, such as those started by the Cria plan. He exhorts the ranchers to likewise evaluate their resultant stock and do as much as possible to expand the Hispano-Arabe breed.

In the past three years, the Cria Caballar have already implemented changes regarding the breeding and commercial viability of the Hispano-Arabe and officially transferred the Stud Book, and all future registration and assessment of the breed, to UEGHa’; the Spanish Union of Cattle Dealers and of Pura Raza Hispano-Arabe. The Hispano-Arabe is now designated as Spain’s Sports Horse with ANCADES.

At government level, MAPA, the Spanish department for Environment and Rural and Marine Affairs, is running a high-profile publicity campaign to heighten awareness of the need for its own people to work towards protecting the breed.

It should also be noted that the outbreeding measures of introducing permissible PRE and Pra’ breeding to improve and expand the Ha’ population could well be removed altogether or retained on a controlled basis, much like the Lipizzaner studs retain a controlled use of PRE stallions, as soon as Spain considers that it has restored the Hispano-Arabe population and breed type to a secure path of pure breeding.

The Hispano-Arabe is a breed in its own right, formally recognised worldwide and given special consideration for protection, hence Spain’s concerted efforts to implement an expanded breeding programme involving reintroduction of Pure Spanish and Arabian bloodlines in an effort to drag the breed back from the edge of extinction.

In the years that Spain has worked hard to promote and save this breed, the Cria has tirelessly visited the United Kingdom to ensure our Hispano-Arabe horses were not lost from the greater plan. Sadly many of the horses they approved and graded in the hope of saving the breed have been lost through failure of this country’s Hispano-Arabe owners to help in continuing with constructive breeding of their horses. Even today, with the added benefit of Calificado approval for artificial insemination to help with next generation (F2) breeding, it appears their plea for help in the preservation of the Hispano-Arabe as a breed is falling upon deaf ears.

It is sincerely hoped that this article will bring home the plight of the Hispano-Arabe breed and the desperate work of the Cria to save it from extinction, and that those of you here in the UK and any other country, involved as owners or breeders, will come to appreciate that what you do now will significantly impact upon the future of the breed as a whole.

Foundation and new generation Hispano-Arabes

As stated in the first part of this article, the Hispano-Arabe horse had been “breeding true” as an indigenous Spanish breed for hundreds of years with consistent, replicable and predictable characteristics, even when occasional out-crossing occurred to improve the breed.

|

The regeneration plan for the Hispano-Arabe involves reinfusing the breed with new bloodlines from the parent pure breeds. In a normal breed improvement plan, the simple breeding of existing Hispano-Arabe horses with the permitted Arabian or Pure Spanish horses would be the system operated. A similar system was operated introducing Clydesdale lines to the Shire horse breeding recovery programme years ago. However, the Hispano-Arabe breeding stock numbers were so critically low that a more radical recovery programme had to be implemented.

A responsible cross-breeding process to produce hybrid F1 and F2, Arabian x Pure Spanish, horses was agreed upon with the intention that, over time, these “new” Hispano-Arabe stock would be bred with each other and with the original Hispano-Arabe bloodlines. In order not to dilute the influence of the parent bloodlines, a percentage blood ratio of Arabian:Spanish was set, permitting a minimum of 25% Arab blood and maximum of 75% Arab blood. As a further evaluation strategy, all existing original Hispano-Arabe breeding stocks, regardless of actual Arabian blood content, were graded for entry to a Foundation Stud Book and rated as being a baseline 50% Arab.

For owners breeding first (F1) and second (F2) generation new Hispano-Arabe horses by the permitted crossbreeding programme, the production of Hispano-Arabe appears to be a very simple endeavour. However, as some early owners discovered when the grading stage was involved, their horses failed to meet the standard for approval in the breeding register.

To produce a Hispano-Arabe, it is not a simple matter of taking any Arabian and breeding it to any pure Spanish horse. Both of these pure breeds have a range of phenotype profiles within their own acceptable breed standard. In the UK, we have a far greater diversity of Arabian horses than Spain has had in her history of the breeding of the Hispano-Arabe. The pure Spanish horse has also been selected to diversify into a heavyweight and a lightweight phenotype in its recent history.

For our UK breeding programme to increase our production of viable Hispano-Arabe youngstock that will meet the grading criteria we have to be selective, using the heavier profile pure Spanish horses and Arabians of Spanish, Polish, Russian and old Crabbet type.

The evaluation criteria that Spain has been fine tuning over the past 30 years takes into account a reasonable range of profile diversity within the new breeding programmes, but it is ultimately travelling towards a more fixed breed type.

|

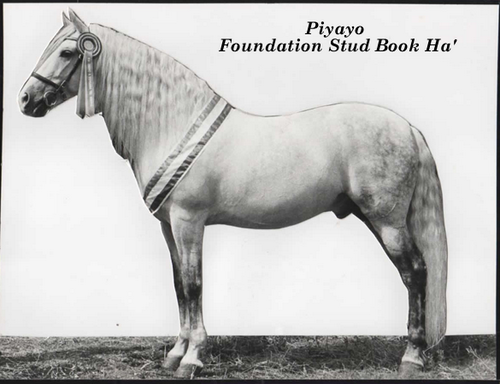

Here in the UK, I have the only foundation Hispano-Arabe bloodlines, Piyayo (Persa PRE x Naveira Ha’). Eventually his progeny will be bred across and infused into the new Hispano-Arabe stock, just as foundation lines in Spain are being used to fix the breed there.

The arbitrary classification of the original foundation horses as 50% Arab carries with it a loaded dice concept with respect to the effect or influence these horses will have upon the Hispano-Arabe stock of true quantifiable Arab ratio. For example, Piyayo on paper is listed in the closed Foundation Stud Book as 50% Arab. In reality when the Arab Horse Society was interested in registering him with them for his sports capability, they could not trace even the required proven 7% Arab they needed to validate him. His pedigree

www.allbreedpedigree.com/piyayo tells the truth about just how much Arab or Spanish influence he carries. But as his genetic coding is the result of generations of blending, it is no longer a simple matter of one or other of the parent breeds having a predictable stamp. To quote the Spanish “He is Hispano-Arabe; neither Arab nor pure Spanish; just what he is: Hispano-Arabe”.

The predictable stamp that he passes down in the outbreeding programme I have had to operate is the original Hispano-Arabe influence. So his two daughters, one out of a Polish Arabian mare and one out of a PRE mare, while registered as respectively 75% and 25% Arab are in phenotype nearer to 50% and 1% Arab. The original Hispano-Arabe fixed geneotype from Piyayo gives all his line a distinctly different profile to other Hispano-Arabe horses of the same documented percentages.

This difference is occurring even more so in Spain given that they have more foundation bloodlines. The influence of these horses has, however, already started to be diversified by the foundation bloodlines at various points, being bred with the new Hispano-Arabe stock, thus steadily producing a levelling off and fixing of a breed standard, as intended.

Piyayo produced three Hispano-Arabe colts, each a potential stallion, from unrelated Arabian mares; none of them were inscribed onto the Hispano-Arabe stud books due to deliberate actions by the appointed registrar of the time. Failure of this country to make full use of the only foundation horse available, and to expand its F1 breeding, means that we are dealing with a future programme that will be dominated by outcross bloodlines and will take far longer to fix the breed standard as a result.

|

In Spain, the Hispano-Arabe breed is still on the critical register for survival so it is highly unlikely that quality breeding horses will find their way to the UK to help improve our genetic pool. Although with Calificardo grading now opening the door to artificial insemination, this new avenue of breed improvement is something I am negotiating with Spain. In recent weeks, we have also traced a productive Hispano-Arabe breeding programme with a daughter stud book in Germany, so hopefully we will be able to facilitate imported lines from this source.

In the meantime, without implementing a draconian breeding programme, I hope that anyone considering breeding will make use of our help and advice in order to ensure the production of viable Hispano-Arabe horses. Apart from breeding for percentage ratio and phenotype, there of course has to be consideration about function and the inheritable multiple-sports ability of the breed.

When naturally breeding from a small gene pool, even with the allowed outside blood, there will be by necessity to fix the breed, a requirement to linebreed or inbreed to prevent dilution while still seeking a balance of breed diversity. To provide advice in this area, I have requested the assistance of the Animal Health Trust geneticists that specialise in and work with other rare equine breeds, such as the Shire horse, that face the same problem of tuning their breed strategy.

|

Fred Barrelet of Beaufort Cottages has also kindly confirmed his interest in providing assistance on veterinary protocol, when required, in dealing with our rare breed future strategies. Such expert support is essential and encouraging, but a very effective and sound selection for fitness to breed exists in the hands of the end user. It is no good breeding for the sake of preservation if the horse does not do more that graze in a field. The Hispano-Arabe is an extremely versatile, intelligent, sociable and fun horse. All our breeding endeavours are ultimately aimed at the everyday rider that can realistically aspire to own for themselves a riding horse that will be a great pleasure to own and ride in any equestrian sphere.

Our work to find and unite the existing and future Hispano-Arabe breeders and owners here in the UK and elsewhere and to give these wonderful horses the recognition and support they deserve is ongoing. While officially establishing our own organisation, we are promoting the breed through various media and a blog link at www.purerazahispano-arabeuk.blogspot.com, so please do not hesitate to contact us if you are interested or have any further enquiries about the Hispano-Arabe.

Published in The Arabian Magazine May 2010 El Shaklan/Spanish Edition